Kristina Rutar was born in 1989 in Slovenia. She completed her postgraduate studies of Interdisciplinary Graphics at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Poland. She lives in Ljubljana where she works as the assistant at the Department of Applied Arts, and teaches a course in ceramics and glass.

The sculptures you make remind us of natural shapes, but they are also transformed into something both dreamy and archetypal. Tell us more about that.

My forms are the result of a combination of two factors: specific creative techniques and the archetypal forms from my dreams. The pottery wheel offers symmetrical, rounded shapes and I was interested in what can be made out of these simple forms. What will happen if I repeat those shapes, if I connect them, if I cut or pierce them? Thus, the final form is made from the multiplied basic building forms.

Alma mater

The form Alma Mater haunted me for years before it came to life. It happened a few times that I slipped into daydreaming about Alma mater by feeling the silhouette of the form. With every daydream the form became clearer and clearer. The dreams stopped abruptly, just at the moment when they materialized. Archetypes are universal for all of us and maybe this is the reason why others also succeed in establishing a relationship with the forms.

Each material has some specific characteristics that artists explore in different ways. For example,you create sculptures from separate units made on the wheel, and then merge them into larger totalities and narratives. You explore ways to distance yourself from established aesthetics and traditional concepts of wheel thrown ceramics.

How would you describe your work proocess and your perception of clay as a material?

Clay can be a liquid and you can pour it, you can give and change the shape until it starts to dry. Once fired, it becomes hard and fragile. If it breaks, the pieces are sharp, which is the complete opposite of softness which clay has while working with it. In the ceramics community one particular view of ceramics as a material took root: it is considered that you have to understand the material and respect it, and this mostly comes down to fully mastering it and avoiding mistakes. I think that this understanding of the material is very superficial. Ceramics is a material that breaks, whatever the reason. Debris and cracks are the most natural properties of clay as the material.

You manage to create an impression of movement in your sculptures. Sometimes you use a thread or cloth which, in combination with the mass of the object, evokes movement and tension… Tell us more about that.

It is natural for me to feel the mass and gravity in the sculpture, I think about it as a part of my creative process. The material we use has its own mass, texture and, most importantly, the sculpture has the third dimension, thanks to which it interacts with space. Hence if mass, gravity, and space are participants in the composition, it is simple to suggest the motion.

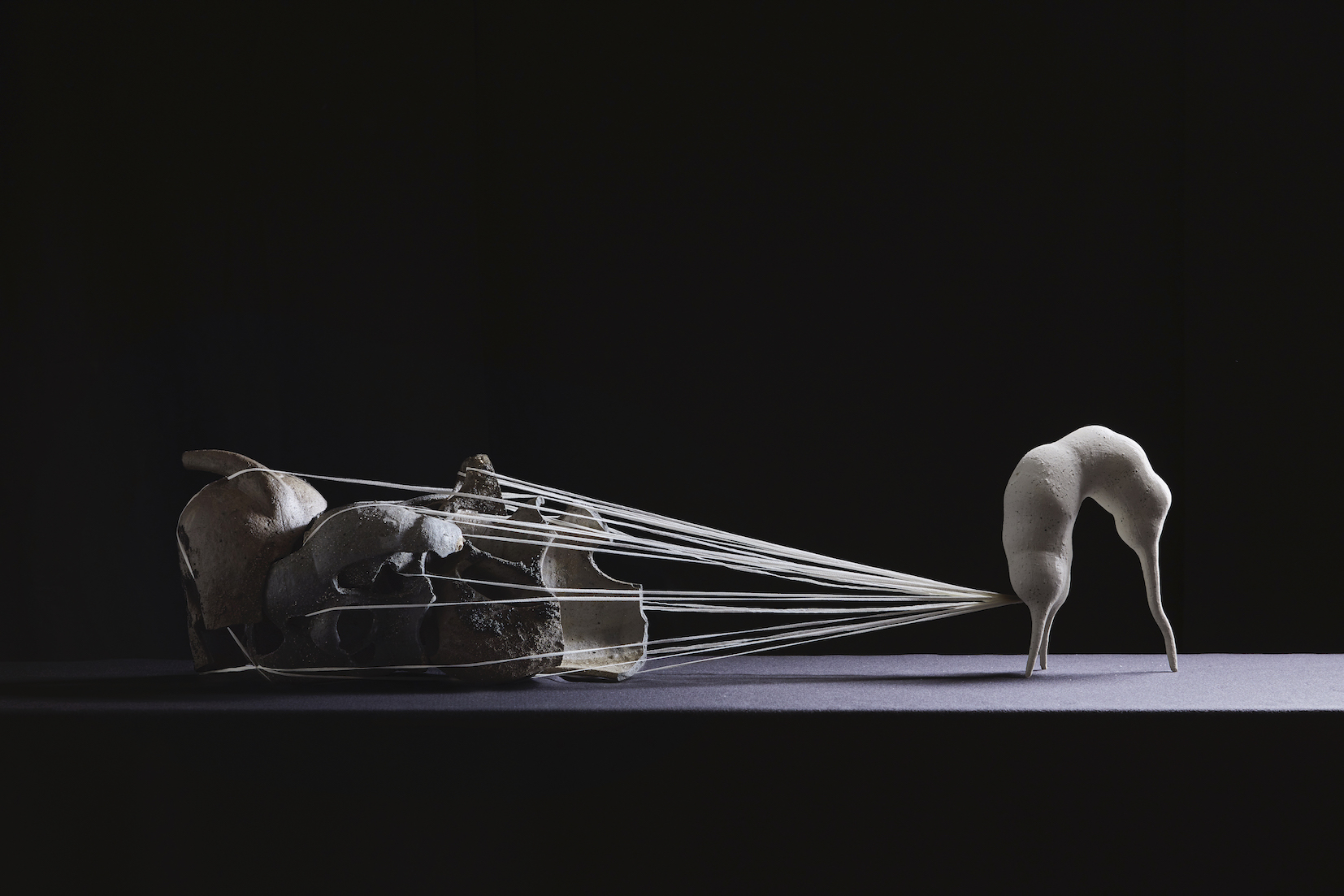

The way I incorporate space into my work to create the impression of movement is based on the use of distances, pauses. In the work Self- portrait, the relationship between two masses is determined by the stretched woolen threads that connect them. What I want to emphasize is not only that mass creates movement – if it cooperates with space, it can generate contexts, narratives, and meanings.

Tell us more about the exhibition On the Origin of Species.

First of all, I feel the need to explain where the idea for this exhibition came from. It happened while I was listening to the album Tomorrow in a year1. The sound of electronics made me feel the movement, growth, flight, storm, evolution. I wondered how I could materialize that feeling. The project was realized in four separate rooms of the Božidar Jakac art gallery. All the rooms were covered with sand that made the steps warm and soft, at the same time absorbing the presence of the other object – a moving visitor.

The first room represents the embryo. Forms hang in veils that create a sense of security. They are fragile and insulated.

The second room represents the embryo during growth – forms develop – cells divide and multiply.

The third room shows empty nests. The end is open, as well as our future. We are constantly adapting to new social and environmental conditions to ensure survival. Empty space opens the field of different interpretations: perhaps the species have matured and left their comfort zone – we don’t know how many of them have survived or what they look like.

The fourth room represents a social commentary on the theme of natural selection and it is a tribute to those who fail to survive. The exhibition space is darkened, a faint light smashing against the debris. I see debris as fragments of former sculptures, but also as a completely new sculpture which tells the story of survival.